Service mapping the digital archiving department at The National Archives

Throughout late 2022 and 2023, I've been introducing service design practices to a small user-centred design team at The National Archives (TNA). The service is responsible for the selection and transfer of digital records (i.e. digital files) into TNA. This includes the capacity for users to associate metadata with individual records to assist with preservation and access or, in the case of sensitive records, to ensure they are 'closed' (i.e. not publicly available).

Shifting perspectives

The main digital product that supports the service is designed and built using the GOV.UK Design System and has recently gone through a service assessment for public beta. During the lead up to the service assessment a lot of team attention was devoted to design decisions at the page and component scale. Alongside day to day design work, my time was also spent working on documentation and increasing the accessibility standards for the product. After we passed our service assessment with glowing colours 💅, we turned to some of the larger scale concerns with the product itself. For example, how to add metadata to individual records for large consignments - i.e. when there are thousands of files and the majority of them need metadata.

Years before this point there had been a lot of discovery work for the product that took into account the end-to-end service journey. But, whilst striding through the service phases (e.g. alpha, beta, etc) the team will unavoidably narrow their perspective toward the details of individual features or pages, particularly when it is a highly technical product. Although this is necessary, you can find yourself stuck in the details when there is a need for a perspective shift away from the product-focus toward the wider service. Another factor that could encourage this shift is the time since the initial research and discovery, during which the product scope may have shifted.

As the designer leading on this product, I recognised the need for a wider viewpoint because more complex design challenges arrived and with that came a lot of unanswered questions about the journey a user takes before they have reached our interface. Working closely with a user researcher I started making a case for some 'taking stock' workshop activities as well as building a service blueprint of the service journey. Something that hadn't been done up to this point.

The value of a service-oriented approach

Within my immediate team and wider department there were no colleagues dedicated to service design activities. This work, like in many places, is conducted at certain moments and responsibility is spread across various disciplines. My proposal to pause active UI design work for new features whilst we expand our service knowledge was met with cautious enthusiasm. I was asked to produce a proposal detailing the activities and benefits of this change. This was a good opportunity to go back to basics and think through the mechanisms and principles, asking tricky questions and disentangling the ideas of 'service design' as a discipline from the ubiquitous activities the whole UCD team engages in whilst designing a service. Speaking to other GOV.UK colleagues it is clear that communicating the value of service design, which often has intangible outputs, is a challenge. And introducing service design where the discipline is not established is particularly difficult because the outputs of the process identify necessary changes at a system level; something that requires buy-in from senior decision-makers.

Below are some of the goals and benefits I identified and communicated in the proposal to design managers. They are quite universal, however I was keen to emphasise the focus on, and collaboration with front-line staff as well as the benefits of zooming out from the product to a system view:

- Create services and products that are as short, efficient and precise as possible

- Identifying time-consuming, burdensome or challenging areas of the service for users and front-line staff

- To build a richer picture of the service ecosystem by using inclusive and collaborative methods

- Surface the experiences of staff or users to identify problems or opportunities in the service

- To create a collective understanding of the end-to-end flow of information and data

- Reduce the repetition of journeys, processes and data entry

- Increase user confidence, reduce journeys that end in dissatisfaction or error, and reduce workload for front-line staff

Determining scope and ambition

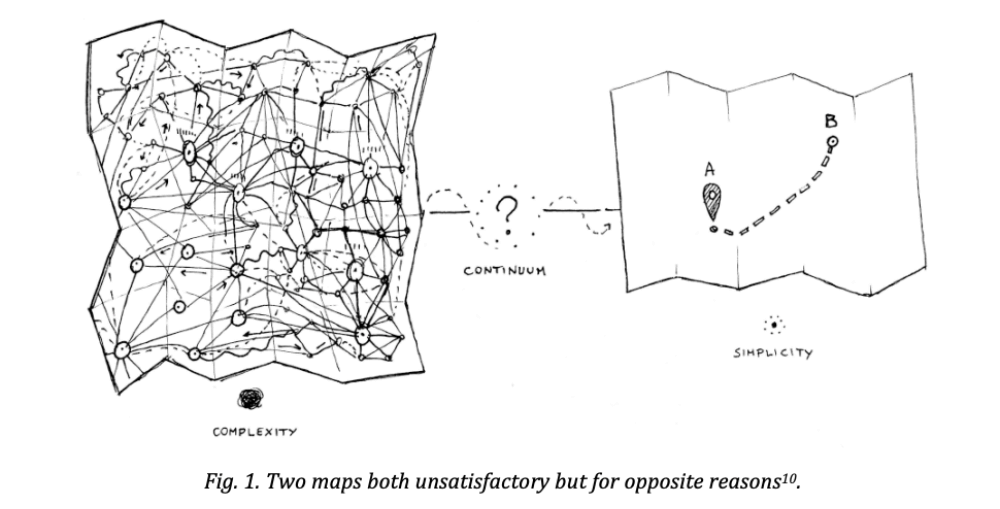

Whilst there is an understandable impetus to try to capture and therefore understand the complexity of a system in as much detail as possible there are good reasons to not do this. For one, any map that tries to replicate the territory on a 1:1 scale is no longer a map. It's a like-for-like representation. Mapping is an intentional simplification and abstraction so that complexity can be more easily understood. The diagram below is a useful reminder of the challenge of choosing where to sit on the complexity to simplicity spectrum:

The diagram is from a paper called Designing Controversies and Their Publics by Tommaso Venturini, Donato Ricci, Michele Mauri, Lucy Kimbell and Axel Meunier.

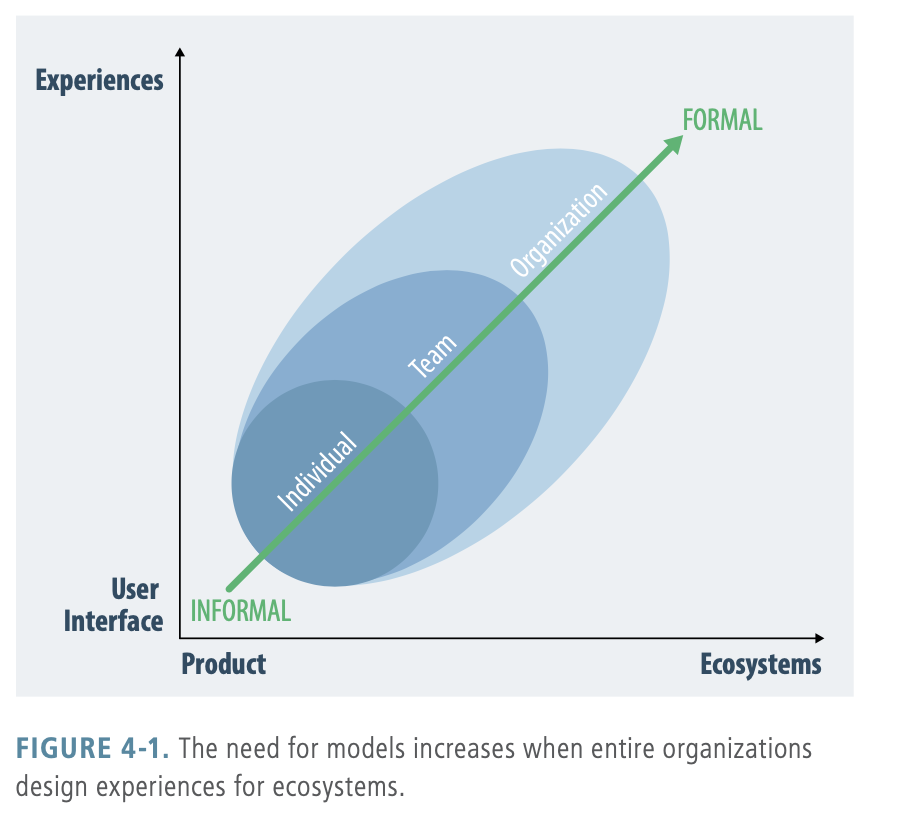

Another diagram (below) from James Kalbach's Mapping Experiences is helpful in understanding the scope and formality of your service mapping ambitions. If you are in a product-focused design team and you are trying to push for time to research and understand user journeys beyond the interface then setting the scope toward the top right of the chart below is important. However, as a pilot activity designed to prove the efficacy of the methods you may need to avoid sprawling scope and ambition. In my case, we had a well targeted and limited ambition to look specifically at how users prepare for a digital transfer. To do this we moved beyond the individual and team scope and researched more of the organisation (i.e. the front and backstage), which connects to the defined user activity.

As stated in the figure caption above, the closer you get to capturing an ecosystem experience, opposed to an interface or product user journey the greater need for more formal modelling (i.e. mapping or visualisation) methods.

Considering all these factors relating to scope and formality helped us validate the need for certain activities with staff and users. It also helped us determine the boundaries of a service mapping exercise. A map was always going to be an outcome of the process, however, when this type of work is unfamiliar to the team or organisation, the license to work on it will be harder to achieve without a clear purpose or hypothesis.

Activities and intended outcomes

The last area I address within the proposal document was a rough outline of the activities involved in building a picture of the service journey. Below are some of those activities and the outcomes. The imagery of the outcomes has been blurred for confidentiality reasons).

Tapping into existing user research

Despite a lot of scope changes the product has been in development and active user research for some time. Discovery work, contextual interviews, etc all contained insights into user actions and pain points. As well as their perspective on the experience of front-stage interactions.

Interviews with front and backstage staff

The most substantial gap in our collective knowledge was from the viewpoint of frontstage staff (those directly communicating with users) and backstage staff (those out of site, but connected to the user experience).

Workshopping a rough service map

A co-creation activity involving a wide range of team disciplines and crucially some of the support staff. Specifically, the front-line staff who are often the glue between the users and organisation, have the widest viewpoint, and will have seen the challenges and failures of the existing system. I could speak a lot about the benefits and nuances of this stage but the most interesting takeaway was that team members from various disciplines who were present and involved in constructing the draft model came away with new and enduring change in perspective on the service as a whole. The key to this was really the rich discussions that revealed many gaps in our knowledge and helped us empathise with the substantial workload of our users and front-line staff.

Service mapping workshop (intentionally blurred)

Service mapping workshop (intentionally blurred)

Drafting, designing, and testing a map

Formalising the knowledge collected in the workshops and user research is not the most complex task, however creates the most tangible (and perhaps engaging) output of the process. The coherent visual arrangement of these elements on a page is important, as is the collective agreement and single reference point to a system view. However the collaboration with user research to make specific editorial decisions about what to include and exclude took the most effort and time. Even at the scale of the diagram above it is hard for an uninitiated colleague to decide what to focus on and how to interpret it. This brings me to the next challenge, which is communicating outcomes and informing decision-making.

Service blueprint (intentionally blurred)

Service blueprint (intentionally blurred)

Informing and narrativising

Narrative is a key means through which people organize and make sense of reality and engage in reasoned argument, particularly when it comes to debating questions of values.

Storytelling and evidence-based policy: lessons from the grey literature

System maps are only useful for those with the time, motivation and pre-existing knowledge to dive into the details. They are also, for the most part, neutral and can be interpreted in many different ways.

The piece of work discussed here started with questions and problems related to a specific product. This product had a neatly siloed domain of use and, apparently, only affected a couple of staff members. The service blueprint I created was enough for me to see how this silo was a fallacy and the product was in fact pushing the workload outward to the users and other departments in the institution. The team who co-produced the blueprint with me were also convinced. However, the larger challenge is how to narrativise this information for other colleagues. This is where the storytelling becomes crucial. My challenge here was to frame the knowledge captured in the processes and diagrams in a way that is accessible and allows for empathy with the users and staff.

I sadly can't show the set of outcomes of this work that demonstrate these principles. These included a co-design workshop and a departmental presentation of findings. However, I can say that the introduction of these new ways of working has successfully expanded the remit of our work beyond a single product and we are moving our focus toward identified areas, which present risk and challenge to the users.

There is also more detail to be shared at some point soon about the co-design workshop, which was an opportunity to prototype some rough ideas for a future-state of the service.